We live in an area of the country where people love to stay healthy and active at all ages. From golf to triathlons, tennis to surfing, pickleball to jiu jitsu, running to softball—one thing is for sure movement makes life more enjoyable! But it’s all fun and games until the pain sets in, and takes up residence in your body, and stops you in your tracks. One of the top indicators that someone is going to get injured is, believe it or not, previous injury. So what's the best way to prevent injury? Not getting injured in the first place! Seems easy enough. One of the things sports have in common is reps. The more reps you put in, the more efficient you become, and the more competitive you are out there on the course, court, etc. Which makes the game interesting and a fun challenge. But how do you know how many reps are too much, to where your body starts to break down and get hurt? You can monitor this yourself through tracking your training workload!

A term you are going to see in this article is ACWR (Acute Chronic Workload Ratio). ‘Acute workload’ is your work out load each week, while your chronic workload is your average workload over 4 weeks time. Why is it important to monitor your training workload? Well the research shows that if you are not managing your work out load properly, you can be at a higher risk for injury! Figuring out your ACWR can help you determine if you are undertraining, overtraining, help you manage your load, and reduce setbacks that come with getting hurt as well as maximize your performance. Pretty good deal!

So what does this actually look like? You are going to take your Below is an example using running:

Runner Schedule:

Week 1: 50 miles

Week 2: 40 miles

Week 3: 50 miles

Week 4: 60 miles

Chronic Training load=50 (Avg miles per week)

ACWR=Weekly mileage / 50

So if we used week 4 for example, your ACWR would be 60/50= 1.2

In recent studies with athletes from various sports, injury risk climbs when this ratio exceeds 1.2, and increases significantly when it exceeds 1.5. This means the bigger swings you have between work out intensity week to week, the greater likelihood that you will have an injury.

Here is an example for the recreational fitness athlete:

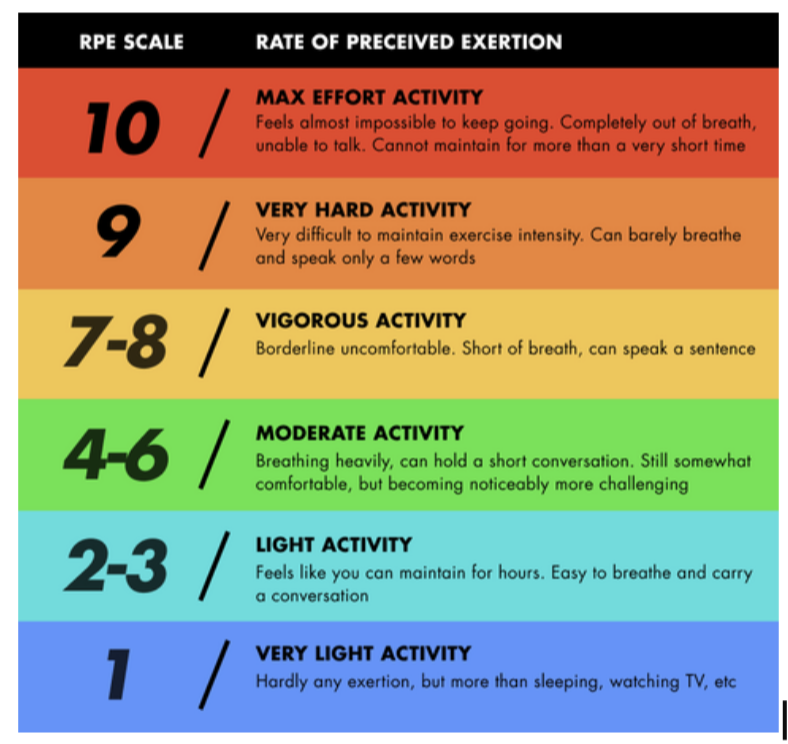

If you don’t have a specific “number” that you are looking at like mileage, another way to calculate your ACWR is using the rate of perceived exertion scale or RPE.

Rate of Perceived Exertion Scale

Where do you fall in your work out?

To calculate your workload, first you are going to record the amount of time that you worked out (or played your sport, etc.) each day of the week. Along with that, go to the RPE scale and decide where you fall on that number line based off how you feel from that work out. These will be your daily multipliers. At the and of the week, add up your scores, and this will be your acute workload of the week (see example below).

Day 1/ Gym 60 mins x RPE (5) =300

Day 2/ Gym 60 mins x RPE (6) =360

Day 3/ Gym 90 Mins x RPE (9) =810

Day 4/ Gym 75 mins x RPE (5) =375

Day 5/ Gym 60 mins x RPE (8) =480

Day 6 / Gym 60 mins x RPE (5) =300

Day 7/ Rest 0 mins x RPE (0) =0

Total= 2,625

**example of 1 week of training, but you would do this for all 4 weeks separately**

You then calculate the average weekly training load for chronic workload.

Week 1= 2,000

Week 2=2,500

Week 3= 2,300

Week 4= 2,625

Chronic Training Load= 2,356.25

Now, you are ready to find your ACWR for each week by dividing the acute (weekly) workload (2,625) by the chronic (4 week) workload. (2,356.25) = 1.11. This would land in your safe training range!

For best practice, research by Gabbett (2016) suggests that there is a “sweet spot” for reducing injury risk of between 0.8 and 1.3. Below an ACWR of 0.8 that injury risk begins to increase again due to undertraining, above 1.3 at risk for overtraining.

Clinically, we see many people who fall into the over or under category with training. Using the ACWR can be a great way for you to determine how to alter workouts when getting back to the gym after an injury. We find that many athletes rehab an injury for 6-8 weeks, and then once they are given clearance to go back to the gym, they shoot for the same level they were working out at prior to their injury, which obviously could cause re-injury! Instead, you should slowly build back up to your previous training load, allowing your body to make adaptations week to week and month to month as it gets stronger and make lasting changes.

If you are not sure where you fall on this spectrum, its never too late to start figuring it out! If pain has been stopping you from doing what you love to do, do NOT hesitate, reach out to us at Athlete’s Mechanic and we will be happy to help you find the best path to get back out there.

Need more help?

Reach out to one of our Physical Therapist’s at Athlete’s Mechanic to help!